Throughout high school and college, my English, Spanish, French, and German teachers carefully steered us away from gay writers, if they could help it, and when they had no choice, tried hard make us believe they weren't. Oscar Wilde's career ended when he was arrested on "scandalous charges." What did he do? Oh. . .um. . .er. . .he corrupted Lord Alfred Douglas, introducing him to gambling and loose women.

They steered us away from all gay content, and when they had no choice, tried their best to make us think it wasn't. Why did Whitman mean by "We two boys together clinging, one the other never leaving"? Oh. . .um. . .er. . .he's talking about his brother, and anyway you're not supposed to read that part.

So I grew up thinking that no novelist, poet, playwright, or artist in all the history of the world had ever been gay. Except one: William Shakespeare.

You could hardly miss the subtexts in practically every play:

1. Romeo and Juliet: Benvolio is in love with Romeo.

2. Merchant of Venice: Antonio is in love with Bassanio.

3. Richard II is gay.

4. Henry IV: Hotspur is gay.

5. Othello: Iago is in love with Othello.

6. A Midsummer Night's Dream: Oberon likes boys, and Puck likes everybody.

Plus his wife, Anne Hathaway, whom he leaves back home in Stratford while he hangs out with guys in London for 20 years

And the Sonnets, addressed to the mysterious "Mr. W. H." and full of complaints about Shakespeare's boyfriend, a fickle youth who is hot one moment, cold another, who spends all his money with no emotional return, and who dates other people -- even women.

How could you miss it?

Mrs. Johnson, who taught my senior-year Shakespeare class, tried to miss it. Desperately. In nearly every class session, she came up with a new bit of evidence that Shakespeare wasn't. . .um, you know, that way (no one ever actually Said the Word).

Her evidence:

1. None of his characters are Wearing Signs.

2. It was an Elizabethan convention to write romantic-sounding poetry about platonic friendship.

3. The "fair youth" was an apprentice who was learning the acting craft.

4. Anne Hathaway was pregnant when they got married.

5. No one who is a writer can ever be. . .um, you know, that way.

6. Especially a great writer.

See also: The 7 Ages of Man

Beefcake, gay subtexts, and queer representation in tv and other pop culture from the 1950s to the present

Feb 16, 2013

Feb 15, 2013

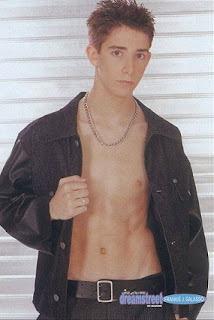

Frankie Galasso: Dream Teen

Every boy band has a leader, a hunk, a goofball, and a "dreamy one," a shy, sensitive, gay-coded prettyboy that the intended audience of preteen girls is expected to swoon over and think "I could change him." Oddly, it's usually the hunk who is gay in real life.

Every boy band has a leader, a hunk, a goofball, and a "dreamy one," a shy, sensitive, gay-coded prettyboy that the intended audience of preteen girls is expected to swoon over and think "I could change him." Oddly, it's usually the hunk who is gay in real life.Dream Street, which drew teen idol attention for a few years in the late 1990s and early 2000s, featured Frankie J. Galasso as the shy, sensitive prettyboy, although he didn't skimp in the beefcake department. His schtick was an unbuttoned shirt, as if he was too shy to take it all the way off, or caught in the midst of dressing, casually revealing his tight chest and killer abs. (And, in this pin-up, his feminine gold ring).

He is also an actor. As a kid, Frankie had a starring role in Hudson Street (1995-96) as cop Tony Danza's son, plus he provided the singing voice of Christopher Robin in two Winnie the Pooh movies.

He has appeared in Jungle 2 Jungle (1997), The Biggest Fan (2002), and A Tale of Two Pizzas (2003).

Since Dream Street folded, Frankie (still in unbuttoned shirts) has embarked on a solo career. In 2012 he toured in the national company of Jersey Boys, about the 1950s boy band Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons. He played the young Joey Peschi, but Jersey Boys has some gay content other than the beefcake, with a gay theatrical manager and a passionate romantic friendship between Frankie and his best friend Tommy.

Every boy band member gets gay rumors. Frankie hasn't addressed them.

Feb 12, 2013

A Separate Peace

Boys at boarding school have been falling in love with each other since Tom Brown's School Days, but for some reason high school teachers -- and homophobic school boards -- never notice. They scream in agony over novels with a brief reference to a gay uncle, but novels about schoolboys in love are perfectly fine.

In the 1970s, my junior high and high school English teachers assigned many homoromances, as Chaim Potok's The Chosen and Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes, but the most overt of them was A Separate Peace (1959), by gay author John Knowles.

In the 1970s, my junior high and high school English teachers assigned many homoromances, as Chaim Potok's The Chosen and Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes, but the most overt of them was A Separate Peace (1959), by gay author John Knowles.

Based upon Knowles' experiences at the elite Philip Exeter Academy, A Separate Peace pairs shy, quiet 16-year old Gene Forrester with the effervescent, carpe-diem Finny.

In the days before teenagers had any idea that same-sex desire existed, Gene can't understand the intensity of his attraction, resulting in envy, jealousy, and anger. He "accidently" breaks Finny's leg, ending his athletic career. Finny forgives him.

Later, Finny falls down a flight of stairs, breaks his leg again, and dies as a result (even today, many novels about gay people kill them as psychic punishment).

When I first read the novel, I couldn't understand why Gene loved and hated Finny at the same time. Today I know about internalized homophobia.

There have been three movie adaptions of A Separate Peace. The producers seemed more gay-savvy than high school English teachers, as they all tried to minimize the homoromance. The 1972 version, which starred John Heyl (who never acted again) and Parker Stevenson (later to star in The Hardy Boys series with Shaun Cassidy), made the boys' uncertain future in World War II pivotal to understanding Gene's rage.

The 2004 version diluted the romance by immersing Gene and Finny into a group of four boys. The 2011 movie short kept all of the competition and removed all of the desire.

In the 1970s, my junior high and high school English teachers assigned many homoromances, as Chaim Potok's The Chosen and Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes, but the most overt of them was A Separate Peace (1959), by gay author John Knowles.

In the 1970s, my junior high and high school English teachers assigned many homoromances, as Chaim Potok's The Chosen and Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes, but the most overt of them was A Separate Peace (1959), by gay author John Knowles.Based upon Knowles' experiences at the elite Philip Exeter Academy, A Separate Peace pairs shy, quiet 16-year old Gene Forrester with the effervescent, carpe-diem Finny.

In the days before teenagers had any idea that same-sex desire existed, Gene can't understand the intensity of his attraction, resulting in envy, jealousy, and anger. He "accidently" breaks Finny's leg, ending his athletic career. Finny forgives him.

Later, Finny falls down a flight of stairs, breaks his leg again, and dies as a result (even today, many novels about gay people kill them as psychic punishment).

When I first read the novel, I couldn't understand why Gene loved and hated Finny at the same time. Today I know about internalized homophobia.

There have been three movie adaptions of A Separate Peace. The producers seemed more gay-savvy than high school English teachers, as they all tried to minimize the homoromance. The 1972 version, which starred John Heyl (who never acted again) and Parker Stevenson (later to star in The Hardy Boys series with Shaun Cassidy), made the boys' uncertain future in World War II pivotal to understanding Gene's rage.

The 2004 version diluted the romance by immersing Gene and Finny into a group of four boys. The 2011 movie short kept all of the competition and removed all of the desire.

Feb 10, 2013

Bell, Book, and Candle

Gillian doesn't like being in the lifestyle. Having to hide all the time, to lie about your identity; the hedonism; the endless affairs. She wants to live a "normal life," with a husband and kids. She falls in love with publisher Shep Henderson and leaves the lifestyle, in spite of the admonitions of her Aunt Queenie and fey "brother" Nicky.

Meanwhile journalist Sidney Redlich is investigating the lifestyle. Most people aren't even aware that people like that exist, he says, but there are hundreds in Manhattan alone. They have their own hangouts, like the Zodiac Club, where the aging queen Bianca de Passe holds court with her many admirers.

Nicky invites Sidney out for a drink and comes out to him -- "You're closer to one than you think." Soon the two are inseparable companions, working on a book together, no doubt lovers as well.

Meanwhile Queenie has fun hinting that she is, um, that way, to see if anyone suspects. No one ever does. "I could say it openly on the bus, and no one would believe me."

Ok, Bell, Book, and Candle (1958) is "really" about witches, one of the witch-as-persecuted-minority vehicles that continued with Bewitched and Sabrina the Teenage Witch. But it couldn't have more gay symbolism if it tried.

Actually, it was trying. The details about "the lifestyle," Gillian's desire to be "normal," Nicky's seduction of Sidney Redlich, and the drag queen aunties all reflected books like The City and the Pillar (Gore Vidal, 1948) and The Homosexual in America (Edward Sangarin, 1952) which were starting to reveal the existence of gay people, "hundreds in Manhattan alone." Playwright Jon Van Druten, who was gay, also wrote I am a Camera (1951), based on Christopher Isherwood's Berlin Stories, about the gay subculture of 1930s Berlin.

Many of the stars had gay connections. Kim Novak (Gillian) attended the parties of 1950s gay Hollywood with Tab Hunter and Rock Hudson. Elsa Lanchester (Queenie) was married to a gay man. Ernie Kovacs (Sidney) portrayed a number of lisping, mincing "pansy" characters on tv. And in 1959 Jack Lemmon (Nicky) would star in the quintessential absurdist gay comedy, Some Like It Hot.

Meanwhile journalist Sidney Redlich is investigating the lifestyle. Most people aren't even aware that people like that exist, he says, but there are hundreds in Manhattan alone. They have their own hangouts, like the Zodiac Club, where the aging queen Bianca de Passe holds court with her many admirers.

Nicky invites Sidney out for a drink and comes out to him -- "You're closer to one than you think." Soon the two are inseparable companions, working on a book together, no doubt lovers as well.

Meanwhile Queenie has fun hinting that she is, um, that way, to see if anyone suspects. No one ever does. "I could say it openly on the bus, and no one would believe me."

Ok, Bell, Book, and Candle (1958) is "really" about witches, one of the witch-as-persecuted-minority vehicles that continued with Bewitched and Sabrina the Teenage Witch. But it couldn't have more gay symbolism if it tried.

Actually, it was trying. The details about "the lifestyle," Gillian's desire to be "normal," Nicky's seduction of Sidney Redlich, and the drag queen aunties all reflected books like The City and the Pillar (Gore Vidal, 1948) and The Homosexual in America (Edward Sangarin, 1952) which were starting to reveal the existence of gay people, "hundreds in Manhattan alone." Playwright Jon Van Druten, who was gay, also wrote I am a Camera (1951), based on Christopher Isherwood's Berlin Stories, about the gay subculture of 1930s Berlin.

Many of the stars had gay connections. Kim Novak (Gillian) attended the parties of 1950s gay Hollywood with Tab Hunter and Rock Hudson. Elsa Lanchester (Queenie) was married to a gay man. Ernie Kovacs (Sidney) portrayed a number of lisping, mincing "pansy" characters on tv. And in 1959 Jack Lemmon (Nicky) would star in the quintessential absurdist gay comedy, Some Like It Hot.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)