During the early 1960s, a lot of cartoons were broadcast during prime time, for audiences of both kids and adults: Yogi Bear, Beany and Cecil, Rocky and Bullwinkle, Top Cat, The Alvin Show. The Flintstones, which premiered in September 1960 at the rather late hour of 8:30 pm, went even farther, with decidedly "mature" plotlines.

It was a remake of Jackie Gleason's Honeymooners series set in a modernized Stone Age, starring two blue-collar quarry workers, Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble, and their wives, Wilma and Betty. Eventually Fred and Wilma had a daughter, Pebbles, and Barney and Betty adopted Bamm-Bamm, a mysterious foundling child who might be an alien.

There were no supporting characters, only a few recurring characters. The camera was focused squarely on the dynamics of the heterosexual nuclear family.

At first, the plots were mostly about misunderstandings, squabbles, and conflict: Fred and Barney want to go bowling instead of going to the opera with their wives; Fred and Barney secretly take dance lessons, but their wives think they are seeing other women.

In later seasons, there weren't many "husbands and wives can't stand each other" plotlines. Instead, we saw fantastic adventures, involving spies, gangsters, aliens, and monsters, usually with the focus on Fred and Barney and the wives relegated to short establishing scenes at the start or finish.

The wives became so irrelevant that you could buy toy sets with figures of Fred's car and Dino, his pet dinosaur, but not Wilma and Betty

After the initial series (1960-66), nine more Flintstones series aired, mostly on Saturday mornings. Some involved Pebbles and Bam-Bam as teenagers, and others involved Fred and Barney by themselves. Wilma and Betty barely mentioned, or not mentioned at all. In the juggernaut of advertising tie-ins that continues to this day, we similarly see no Wilma or Betty, just Fred selling Flintstones Vitamins or Barney trying to trick Fred out of his Pebbles Cereal.

Maybe they realized that their primary emotional attachment was with each other, and now they see the ex-wives only when they go to pick up the kids for the weekend.

See also: Yogi Bear and The Three Stooges.

Beefcake, gay subtexts, and queer representation in tv and other pop culture from the 1950s to the present

Aug 4, 2018

Aug 3, 2018

Not the Marrying Kind: Gay Burns and Allen

Television was introduced in 1949, just in time for the formative years of the first Boomers (the generation officially started in 1945). Radio performers scrambled to make the transition. Some made it, most didn't. Burns and Allen, a "married couple" sitcom starring comedians George Burns and Gracie Allen, made it. After 20 years on radio, they transitioned to television in 1950 and stayed on until 1958, stopped only by Gracie's death.

Television was introduced in 1949, just in time for the formative years of the first Boomers (the generation officially started in 1945). Radio performers scrambled to make the transition. Some made it, most didn't. Burns and Allen, a "married couple" sitcom starring comedians George Burns and Gracie Allen, made it. After 20 years on radio, they transitioned to television in 1950 and stayed on until 1958, stopped only by Gracie's death.They're shown here with guest star Steve Reeves.

I recently listened to an episode from the end of the radio run, in 1949.

The homophobic silence of Dark Age America was starting to break -- very, very slightly -- as radio sought to compete with television by introducing "racy" content -- hints and innuendos about sex in general, and same-sex desire in particular. So there are gay jokes.

The plot is about George and Gracie, playing themselves, trying to find a wife for painfully shy next door neighbor, musician Meredith Willson (who penned The Music Man).

They co-opt singer Eddie Cantor (who was subject to some gay rumors of his own). He wants to marry off some of his daughters.

So Gracie invites Eddie Canter over, and announces to Meredith, "We've found someone for you to marry!"

After a pause, Meredith says: "Gee, I had my heart set on a woman."

Later Eddie explains to his potential son-in-law how a wedding works:

"The minister says 'I now pronounce you man and wife, and then you kiss."

"Even if you've just met?" Meredith asks, thinking that he means kissing the minister.

Meredith (or at least the character he is playing) is too shy to talk to women, let alone marry one. He complains: "I can't get married if a woman is [at the wedding]."

Again and again, joke after joke brings up the idea that Meredith is considering marrying a man.

What's going on?

If same-sex desire is really beyond the boundaries of what can be known, then the characters are playing with an absurdity, a play on words like Abbott & Costello's "Who's on First" routine.

But same-sex desire was known, even in 1949. The Kinsey Report, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948) revealed its existence to millions. George Burns and Gracie Allen knew gay people, worked with gay people in Hollywood.

Their television series often implied that teenage son Ronnie Burns (or at least the character he played) preferred the company of men.

Maybe that's why Meredith Wilson's character trips easily over the boundary between "confirmed bachelor" and "gay."

At the end of the episode, everyone agrees that he "should never get married." At least not to a woman.

Even in the darkest of the Dark Ages, there were still hints and innuendos.

(In real life, Meredith Wilson was married three times. To women.)

See also: Eddie Cantor: The Craziest Reason for Gay Rumors

Boxing: Your Grandfather's Beefcake Sport

During the first half of the twentieth century, boxing was very popular, probably more popular than what would become the big name sports of baseball, basketball, and football.

It makes sense during the Depression: you don't need a lot of expensive equipment, there's no team demanding salaries, just two guys duking it out in a ring.

They had their shirts off, of course, and they usually wore skimpy boxing trunks, giving your grandfather's generation their beefcake quot.

The homoeroticism of two muscular, sweaty guys putting their hands on each other is obvious.

It was a male-only sport, but boys of all ages played.

It wasn't unusual to see elementary school kids in the ring.

Every high school had its boxing team. So did boys' clubs, the YMCA.....

Military bases, summer camps, the Civilian Conservation Corps...

...and private boxing clubs in every city.

The Golden Gloves, amateur boxing competitions, were held in New York and Chicago beginning in 1925, although the National Golden Gloves didn't get its start until 1962.

Today you rarely see amateur boxing clubs. Only one or two high schools offer boxing, and those are from recent attempts to restore the sport.

It seems old fashioned and decidedly Eurocentric in an era of caopeira, Muay Thai, Mongolian bokh, and mixed martial arts.

It makes sense during the Depression: you don't need a lot of expensive equipment, there's no team demanding salaries, just two guys duking it out in a ring.

They had their shirts off, of course, and they usually wore skimpy boxing trunks, giving your grandfather's generation their beefcake quot.

The homoeroticism of two muscular, sweaty guys putting their hands on each other is obvious.

It was a male-only sport, but boys of all ages played.

It wasn't unusual to see elementary school kids in the ring.

Every high school had its boxing team. So did boys' clubs, the YMCA.....

Military bases, summer camps, the Civilian Conservation Corps...

...and private boxing clubs in every city.

The Golden Gloves, amateur boxing competitions, were held in New York and Chicago beginning in 1925, although the National Golden Gloves didn't get its start until 1962.

Today you rarely see amateur boxing clubs. Only one or two high schools offer boxing, and those are from recent attempts to restore the sport.

It seems old fashioned and decidedly Eurocentric in an era of caopeira, Muay Thai, Mongolian bokh, and mixed martial arts.

Aug 2, 2018

The Marx Brothers: Bisexual Groucho and hunky Chico

I first saw the Marx Brothers at a Film Festival during the Summer of 1978 (along with Animal House, Grease, and The Rocky Horror Picture Show: it was a memorable summer). The anarchic comedians came from Vaudeville, moved onto Broadway, and started spinning their bits into movie comedy with Cocoanuts (1929). Three of the greatest comedies of all time followed: Animal Crackers (1930), Monkey Business (1931), and Horse Feathers (1933). Then they made some movies that were merely great.

Zeppo, the youngest, played the "handsome leading man" for a treacly romantic plot.

Groucho engaged in long cons, often involving wooing wealthy dowager Margaret Dumont.

Chico (right) played an Italian-accented musical virtuoso planning cons of his own.

Harpo played his mute, addled sidekick, who liked to chase women while honking a horn. He also handed random people his leg.

Wait -- Zeppo falling in love with a woman, Groucho wooing a woman, Harpo chasing women. Granted, the wordplay came fast and furious, pretensions were deflated, social institutions were mocked -- but wasn't it still heterosexist?

Not at all. You can queer a Marx Brothers movie as easily as Making Love.

1. You don't expect a lot of beefcake in movies from the 1930s, but there was some. Mostly from incidental players.

In this still from Duck Soup, Zeppo looks pleasantly muscular for the 1930s, and Chico positively buffed.

2. In the heart of the Pansy Craze, there are no pansy jokes No screaming queens, no effeminate waiters, none of the overt homophobia evident in other movie comedies of the era.

3. Zeppo's hetero-romance is ludicrously over-the-top; it is one of the social institutions that the Marx Brothers are mocking.

Groucho woos Margaret Dumont for her money; elsewhere, his jabs and hints hit men and women both. "Tell me, what do you think of the traffic problem? What do you think of the marriage problem? What do you think of at night when you go to bed, you beast!"

Harpo hands his leg to women and men both.

Chico doesn't seem particularly interested in women.

All of the Marx Brothers demonstrate an easygoing nonchalance about same-sex desire that is remarkable for the period.

4. In real life, Groucho stated that he was "straight but curved around the edges."

My friend Randall claimed to have been with him at a party in Hollywood in 1958.

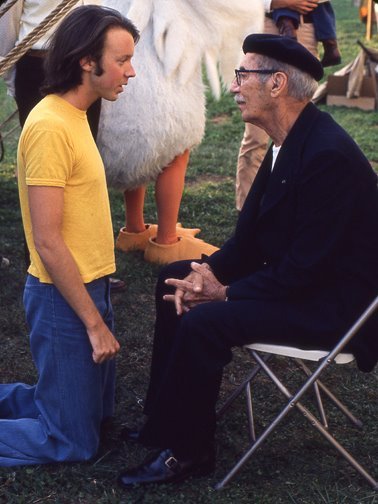

Near the end of his life, the 80-year old Groucho fell in love with 30-year old Bud Cort -- who starred in Harold and Maude (1971), about a romance between a teenage boy and an elderly woman. Bud moved into Groucho's mansion, where the question of whether they became physically intimate is nobody else's business. "I loved him, and he loved me. He was my fairy godfather."

See also: Dick Sargent, Cary Grant, and Groucho Marx in the Same Bed.

Groucho engaged in long cons, often involving wooing wealthy dowager Margaret Dumont.

Chico (right) played an Italian-accented musical virtuoso planning cons of his own.

Harpo played his mute, addled sidekick, who liked to chase women while honking a horn. He also handed random people his leg.

Wait -- Zeppo falling in love with a woman, Groucho wooing a woman, Harpo chasing women. Granted, the wordplay came fast and furious, pretensions were deflated, social institutions were mocked -- but wasn't it still heterosexist?

Not at all. You can queer a Marx Brothers movie as easily as Making Love.

1. You don't expect a lot of beefcake in movies from the 1930s, but there was some. Mostly from incidental players.

In this still from Duck Soup, Zeppo looks pleasantly muscular for the 1930s, and Chico positively buffed.

2. In the heart of the Pansy Craze, there are no pansy jokes No screaming queens, no effeminate waiters, none of the overt homophobia evident in other movie comedies of the era.

3. Zeppo's hetero-romance is ludicrously over-the-top; it is one of the social institutions that the Marx Brothers are mocking.

Groucho woos Margaret Dumont for her money; elsewhere, his jabs and hints hit men and women both. "Tell me, what do you think of the traffic problem? What do you think of the marriage problem? What do you think of at night when you go to bed, you beast!"

Harpo hands his leg to women and men both.

Chico doesn't seem particularly interested in women.

All of the Marx Brothers demonstrate an easygoing nonchalance about same-sex desire that is remarkable for the period.

4. In real life, Groucho stated that he was "straight but curved around the edges."

My friend Randall claimed to have been with him at a party in Hollywood in 1958.

Near the end of his life, the 80-year old Groucho fell in love with 30-year old Bud Cort -- who starred in Harold and Maude (1971), about a romance between a teenage boy and an elderly woman. Bud moved into Groucho's mansion, where the question of whether they became physically intimate is nobody else's business. "I loved him, and he loved me. He was my fairy godfather."

See also: Dick Sargent, Cary Grant, and Groucho Marx in the Same Bed.

Jul 29, 2018

Tales of Boys and Men: Robert Louis Stevenson

Strangely, I always associate Christmas Day with boredom. Opening and playing with your presents takes about an hour, Christmas dinner takes another hour, leaving fourteen hours to sit around the house, with no school, friends incommunicado, bad weather outside, and nothing on tv.

The Black Arrow (1888) was a heterosexual romance, but The Master of Ballantrae (1889) is about two brothers, James Durie and his brother Harry, on opposite sites of the Jacobite Rebellion. There's some heterosexual romance, but the emphasis is on the enmity between the two brothers melting into love. They die the same hour, and are buried under the same stone.

Bisexual Errol Flynn (left) starred in a famous 1953 version.

Time to break out your stash of Robert Louis Stevenson books.

The Scottish novelist (1850-1894) is relegated to the junior high classroom nowadays, probably because his works aren't usually heterosexist.

His two main subtext novels both involve bonds between teenage boys and adult men:

Treasure Island (1883), an adventure with pirates and buried treasure in the South Seas, originally serialized in the magazine Young Folks, deliberately written with "no women in it." No heterosexual imaginings, but young Jim Hawkins develops a grudging friendship with Long John Silver.

My favorite version was full of beefcake illustrations by N.C. Wyeth.

In every generation, the current Hollywood It-boy seems to get a chance to play Jim Hawkins: Jackie Cooper (1934), Bobby Driscoll (1950, left), Kim Burfield (1972), Christian Bale (1990, above), and Kevin Zegers (1999).

My favorite version was full of beefcake illustrations by N.C. Wyeth.

In every generation, the current Hollywood It-boy seems to get a chance to play Jim Hawkins: Jackie Cooper (1934), Bobby Driscoll (1950, left), Kim Burfield (1972), Christian Bale (1990, above), and Kevin Zegers (1999).

Kidnapped (1886): David Balfour, tricked out of his inheritance by a villainous uncle, travels the rough Scottish Highlands, where he is rescued by and buddy-bonds with the rogueish Alan Breck. Again, "no women in it."

David has been played by Freddie Bartholomew (1938), James MacArthur (1960), Lawrence Douglas (1971), Brian McCardie (1995), and Anthony Pearson (2005). Some versions give him a girlfriend.

This photo is actually from The Light in the Forest, but I couldn't resist including a shirtless shot of James MacArthur.

A statue commemorating David and Alan Breck has been erected in Edinburgh.

Some scholars also find a subtext in The Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), but I didn't see one.

The Black Arrow (1888) was a heterosexual romance, but The Master of Ballantrae (1889) is about two brothers, James Durie and his brother Harry, on opposite sites of the Jacobite Rebellion. There's some heterosexual romance, but the emphasis is on the enmity between the two brothers melting into love. They die the same hour, and are buried under the same stone.

Bisexual Errol Flynn (left) starred in a famous 1953 version.

So, was Robert Louis Stevenson gay? According to his biography, Myself and the Other Fellow, by Claire Harmon, no, but he appreciated homoerotic desire, and he enjoyed the attention of the many gay men who were drawn to him.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)