It was about an unnamed family -- mom, young adult daughter, teenage son, younger son -- drawn in grotesquely realistic detail.

They spoke in nearly incomprehensible slang and had bizarre customs. There was an "ice box" instead of a refrigerator, a gigantic radio instead of a tv. They bathed in a tub in the kitchen.

The older son had a job, though he looked barely fifteen.

Confused, repelled, yet fascinated, I tried to decipher the strips day after day, week after week. The world they portrayed was vastly different from the world I knew.

Boys in my world were always fully clothed, except in locker rooms, but in Out Our Way, they stripped down for baths and for bed and to swim. They displayed a remarkable physicality, an awareness of the way their bodies looked and felt and moved.

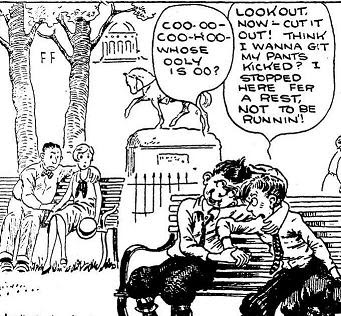

Boys in my world did not touch each other, except during sports matches and fights. We were expected to find physical contact abhorrent. But in Out Our Way, boys un-selfconsciously pressed against each other, draped their legs over each other's bodies, hugged, slept in the same bed

Boys in my world were expected to groan with longing over the girls who walked in slow-motion across the schoolyard, their long hair blowing in the wind. They were expected to evaluate the hotness of actresses on tv, discuss breasts and bras, and claim innumerable sexual conquests. But boys in Out Our Way never displayed the slightest heterosexual interest. Instead, they consistently mocked the silliness of heterosexual romance.

What sort of world was this?

Many years later, I found that the comics I was reading were reprints from the 1930s, and even then, many had been nostalgic, evoking the author J.R. Williams' childhood at the turn of the century.

I was gazing into a time capsule, into a era when heterosexual desire was expected to appear at the end of adolescence, not at the beginning, so teenage boys were free from the "What girl do you like?" chant.

The family's name was the Willetts. The youngest was nicknamed "The Worry Wart." Because his antics caused the adults to worry.

ReplyDeleteCould somebody translate that last one?

ReplyDeleteI think "ooly" is a nonsense term, and "get my pants kicked": the other boy is worried that he will get beat up by passersby who suspect him of being gay.

Delete* pretty sure "ooly" is mock-babytalk/slang for either "dolly", or "girly" (via "goilly"), given the context that they seem to be making fun of the couple behind them.

DeleteI never thought of that. Maybe he's worried about getting beat up for making fun of the couple, not for an implication of gayness.

Deletecould be a bit of both? my read on it was also that the boy was uncomfortable "acting like a sissy". would "getting my pants kicked" be something an adult stranger would do (given the era), or would that be more of a "getting beaten up" (by other boys) thing?

DeleteWell, country boys, you know?

ReplyDeleteBy the way, is it weird to me that Indians in the Westerns sound like they're speaking Papua New Guinea pidgin? Replacing some racially insensitive words with other racially insensitive words?

My generation had the same book thing, though boys also put books over their groins. And there were certain ways to cross your legs. (A lady never sat in anything resembling a lotus position.)

Don't know if this has been mentioned before, but the book We Boys Together: Teenagers in Love Before Girl-Craziness, by Jeffery P. Dennis, sounds interesting. I haven't read it myself (and it's a bit pricey), but the description says: "Before World War II, only sissies liked girls. Masculine, red-blooded, all-American boys were supposed to ignore girls until they were 18 or 19. Instead, parents, teachers, psychiatrists, and especially the mass media encouraged them to form passionate, intense, romantic bonds with each other.

ReplyDeleteThis book explores romantic relationships between teenage boys as they were portrayed before, during, and immediately after World War II."

I highly reoommend it.

ReplyDelete