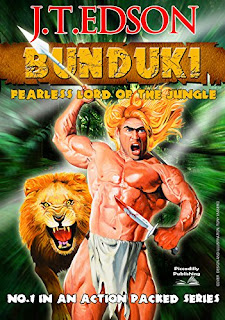

If you're a Tarzan purist, trying to collect everything about the Lord of the Junble, you might want to pick up (but not read) Bunduki, a series about "the fearless lord of the jungle" by J.T. Edson (not Edison).

If you're a Tarzan purist, trying to collect everything about the Lord of the Junble, you might want to pick up (but not read) Bunduki, a series about "the fearless lord of the jungle" by J.T. Edson (not Edison).A British writer and right-wing goofball (1928-2014), Edson wrote mostly Westerns, and continued long after the genre stopped being popular, creating such "renowned" characters as Dusty Fog and the Ysabel Kid.

Two have been made into movies, Trigger Fast (1994), and Guns of Honor (1994), with Christopher Atkins playing Dusty Fog.

I don't know about the movies, but the novels are intensely homophobic, full of simpering gay-stereotype villains, and racist, promoting the myth that slavery was a benevolent system; most slaves were loyal to their masters, and rose to defend them against evil "Northern aggression."

So it's not clear why the Burroughs estate licensed Edson to use the Tarzan characters. He didn't write science fiction, and he was a wacko.

So it's not clear why the Burroughs estate licensed Edson to use the Tarzan characters. He didn't write science fiction, and he was a wacko.But they did, and Bunduki appeared in 1975, followed by Bunduki and Dawn and Sacrifice for the Quagga God. Then the estate got tired of the Tarzan name being attached to such rubbish, so they forbade Edson from using Tarzan, Jane, or Korak in future stories. The fourth novel, Fearless Lord of the Jungle, omits any Tarzan references, and the last novel was unpublished.

Bunduki is part of the Wold-Newton Universe, where Philip Jose Farmer interconnects all of the fictional heroes, from Alan Quartermaine to Sherlock Holmes, as part of one extended family. He was adopted by the aging Lord Greystoke after his parents were killed in the dreadful Mau Mau uprising in Kenya in the 1950s.

Later he married Dawn, Lord Greystoke's great-granddaughter, and they were zapped off to the planet Zillikian together.

Zillikian is completely Earthlike, with flora and fauna identical to Earth's jungles (with a few additions, like bears and giant snakes), plus jibbering savages, slave traders, a female despot, and effeminate traders to fight. It is the Africa of Edgar Rice Burroughs' original myth. All it needs is a loincloth-clad vine-swinger with flowing golden hair to rescue the damsel in distress.

The novels were all reprinted by Piccadilly Publishing in 2016. I suggest buying them for the cover art, but not reading the text inside.